I work with GPUs at work every day, but I’ve always struggled to really understand what’s happening under the hood. Most of my work is through high-level libraries and frameworks, which abstract away all the scheduling, memory hierarchies, and execution details. I knew GPUs were fast, but I didn’t really understand why.

At university, exercises in reverse engineering CPUs really helped me understand cache hierarchies, instruction latencies, and performance quirks. I decided to try something similar on an Nvidia Jetson Orin Nano: treat the GPU as a black box and reverse engineer its microarchitecture through simple experiments.

I’m by no means an expert in GPUs, this is me poking at the Jetson Nano to see what I can learn.

Table of Contents

Part 1: Warp Size

A warp is a group of threads that a GPU executes simultaneously in lockstep on a single Streaming Multiprocessor (SM). All threads in a warp execute the same instruction at the same time, and if some threads take a different branch, the SM serializes execution until they converge. In our first micrbenchmark, we’ll try and deduce the size of a warp:

Idea: Threads in a warp execute instructions in lockstep. If the control flow diverges between threads in a warp, the Streaming Multiprocessor will serialize execution until the threads converge again. Divergent code can therefore slow things down, and I’ll use this behavior to my advantage.

The kernel I designed splits threads into groups of size N. Threads in the same group perform the same instructions. By varying N and measuring execution time, we can find an N that minimizes the kernel runtime. That N is the warp size (or a multiple of it):

__global__ void divergent_kernel(unsigned long long clock_count, unsigned long long *out, int N) {

// Calculate which group the current thread belongs to:

int group = threadIdx.x / N;

for (int i = 0; i < (2<<20); i++) {

if (group == i) {

unsigned long long start = clock64();

while (clock64() - start < clock_count) {

// spin

}

out[threadIdx.x] = clock64();

}

}

}

Threads within a warp execute in lockstep until they reach the if (group == i) condition. If any thread in a warp belongs to group i, all other threads in the warp that are not part of this group must wait until it finishes, effectively serializing execution. Here, each thread spins for a predetermined number of cycles (100 million). The kernel runs fastest when all threads belong to the same group, indicating that N is the warp size or a multiple of it.

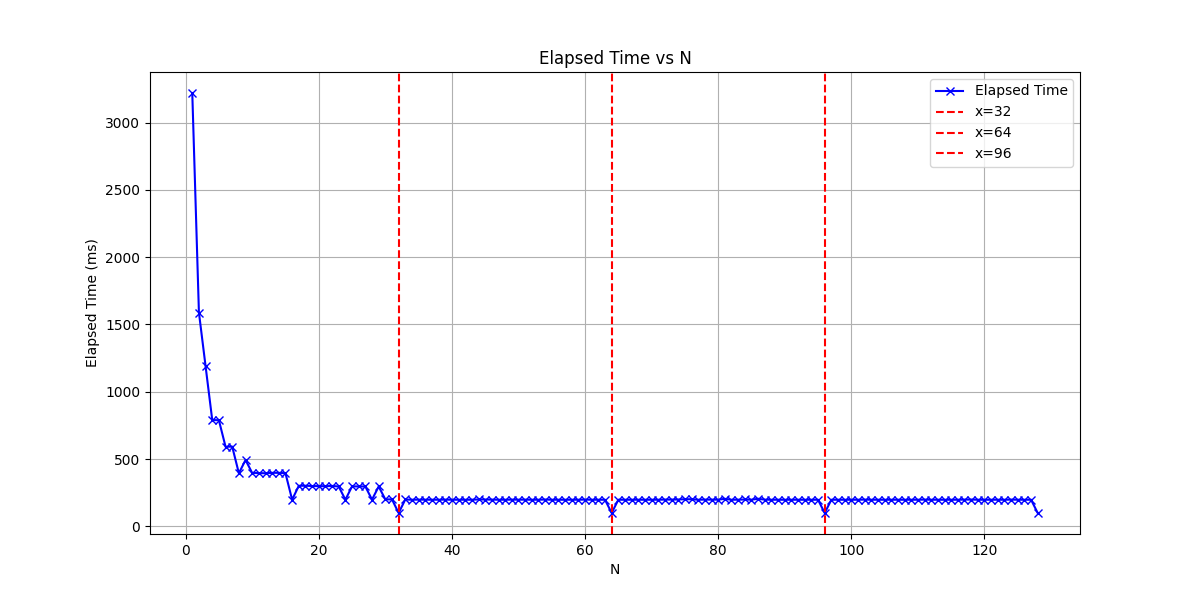

Timing the execution for increasing values of N yields the following results:

There are clear valleys at 32 and its multiples, indicating that the warp size is 32 threads.

Note: This first part was more of a warm-up, unsurprisingly, all modern Nvidia GPUs have a warp size of 32.

Part 2: Streaming Multiprocessors

Part 2.1 Number of Streaming Multiprocessors

Streaming multiprocessors [SMs] are a fundamental unit of compute in Nvidia GPUs. Conceptually, an SM is similar to a CPU core in that they are the smallest unit on a chip that contains all the hardware needed to perform a thread of execution (arithmetic/logic units, caches, registers, schedulers, etc.).

During Execution, the CUDA runtime maps a block to a single SM. Multiple Blocks can be assigned to the same SM.

To determine the number of SM our GPU has we can read values in the special purpose register %smid which contains the id of the Streaming Multiprocessor that the thread is running on. we start 64 blocks (this should be much larger than the total number of SMs) and track to see which SM they are executed on:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

#include <cuda.h>

#include <stdio.h>

__global__ void smid_kernel(int *smids) {

unsigned int smid;

asm("mov.u32 %0, %smid;" : "=r"(smid));

smids[blockIdx.x] = smid;

}

int main() {

size_t N = 64; //Number of blocks we will launch

std::vector<int> smid_h(N);

int* smid_d;

cudaMalloc(&smid_d, N * sizeof(int));

cudaMemcpy(smid_d, smid_h.data(), N * sizeof(int), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

smid_kernel<<<N, 1>>>(smid_d);

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

cudaMemcpy(smid_h.data(), smid_d, N * sizeof(int), cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

std::cout << smid_h[i] << ", ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

}

The output of the above code is as follows:

0, 0, 2, 2, 4, 4, 6, 6, 1, 1, 3, 3, 5, 5, 7, 7, 0, 0, 2, 2, 4, 4, 6, 6, 1, 1, 3, 3, 5, 5, 7, 7, 0, 0, 2, 2, 4, 4, 6, 6, 1, 1, 3, 3, 5, 5, 7, 7, 0, 2, 4, 6, 1, 3, 5, 7, 0, 2, 4, 6, 1, 3, 5, 7,

Blocks are executed on streaming multiprocessors 0-7, indicating our Nvidia GPU has 8 Streaming Multiprocessors. Note the pattern in how blocks are assigned to SMs 0,0,2,2,4,4,6,6,1,1..... We will look at this in more detail later when dissecting the block scheduler.

Part 3: CUDA cores per Streaming Multiprocessors

Although an SM can be thought of being conceptually similar to CPU cores, their power comes from the fact that they can executed many threads in parallel, instead of just the 1 or 2 of a traditional CPU. A single SM can have many active threads, each one potentially making progress in each clock cycle.

Idea: To estimate the number of CUDA cores per SM, we will launch a compute intensive kernel for varying number of threads per SM, this kernel will be designed such that every thread completely saturates the arithmetic unit of a single CUDA core. We will launch an increasing number of threads on a single SM and time of the kernel’s execution. We should see a the kernel execution time look like a function with clear steps, each step happening when we’ve completely saturated all CUDA cores within a SM.

To completely saturate the arithemetic unit within a CUDA core we will use the FMA instruuction. For our calculations, we first need to know what the instruction latency of an FMA is and how many independent FMAs can be issues per cycle per CUDA core.

Part 3.1: FMA latency and throughput

To measure instruction latency of an FMA instruction, we can construct a kernel with many FMA instructions and Read-after-Write dependencies between them:

__global__ void fma_latency (unsigned long long *cycles, long iterations, float init, float mul, float add) {

if (threadIdx.x != 0) return;

volatile float x = init;

unsigned long long start = clock64();

#pragma unroll 128

for (int i = 0; i < iterations; i++) {

x = __fmaf_rn(x, mul, add);

}

unsigned long long end = clock64();

cycles[0] = end - start;

cycles[1] = __float_as_uint(x);

}

The result must be written to the output array to prevent the compiler from optimizing away the operations.

.visible .entry _Z11fma_latencyPylfff(

.param .u64 _Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_0,

.param .u64 _Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_1,

.param .f32 _Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_2,

.param .f32 _Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_3,

.param .f32 _Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_4

)

{

.reg .pred %p<7>;

.reg .f32 %f<144>;

.reg .b32 %r<3>;

.reg .b64 %rd<24>;

ld.param.u64 %rd10, [_Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_1];

ld.param.f32 %f143, [_Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_2];

ld.param.f32 %f9, [_Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_3];

ld.param.f32 %f10, [_Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_4];

mov.u32 %r1, %tid.x;

setp.ne.s32 %p1, %r1, 0;

@%p1 bra $L__BB0_9;

// begin inline asm

mov.u64 %rd11, %clock64;

// end inline asm

setp.lt.s64 %p2, %rd10, 1;

@%p2 bra $L__BB0_8;

add.s64 %rd12, %rd10, -1;

and.b64 %rd2, %rd10, 127;

setp.lt.u64 %p3, %rd12, 127;

@%p3 bra $L__BB0_5;

sub.s64 %rd22, %rd2, %rd10;

$L__BB0_4:

.pragma "nounroll";

fma.rn.f32 %f12, %f143, %f9, %f10;

fma.rn.f32 %f13, %f12, %f9, %f10;

fma.rn.f32 %f14, %f13, %f9, %f10;

...

add.s64 %rd22, %rd22, 128;

setp.ne.s64 %p4, %rd22, 0;

@%p4 bra $L__BB0_4;

$L__BB0_5:

ld.param.u64 %rd19, [_Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_1];

and.b64 %rd18, %rd19, 127;

setp.eq.s64 %p5, %rd18, 0;

@%p5 bra $L__BB0_8;

ld.param.u64 %rd21, [_Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_1];

and.b64 %rd20, %rd21, 127;

neg.s64 %rd23, %rd20;

$L__BB0_7:

.pragma "nounroll";

fma.rn.f32 %f143, %f143, %f9, %f10;

add.s64 %rd23, %rd23, 1;

setp.ne.s64 %p6, %rd23, 0;

@%p6 bra $L__BB0_7;

$L__BB0_8:

ld.param.u64 %rd17, [_Z11fma_latencyPylfff_param_0];

cvta.to.global.u64 %rd14, %rd17;

// begin inline asm

mov.u64 %rd13, %clock64;

// end inline asm

sub.s64 %rd15, %rd13, %rd11;

st.global.u64 [%rd14], %rd15;

mov.b32 %r2, %f143;

cvt.u64.u32 %rd16, %r2;

st.global.u64 [%rd14+8], %rd16;

$L__BB0_9:

ret;

}

Running this kernel for sufficiently many iterations results in the following output:

(base) umarkar@umarkar-desktop:~/Documents/microbenchmark_jetson_nano$ ./build/fma_latency

cycles per FMA: 4.09486

Indicating that the SM on our GPU has an instruction latency of 4 cycles per FMA.

Similarly, to determine how many FMA instructions can be issued per cycle, we construct a kernel with many independent FMA instructions in an attempt to saturate the CUDA core and always have an instruction ready to be issued. The following kernel is constructed in such a way that there are 8 independent “streams” of calculation, I’m making an assumption that we will not be able to issue more than 2 instructions per cycle, so this kernel should be able to completely saturate the ALU.

__global__ void fma_throughput(unsigned long long *out, int iters) {

float a0=1.0f, a1=2.0f, a2=3.0f, a3=4.0f, a4 = 4.0f, a5=5.0f, a6=6.0f, a7=7.0f;

float b=2.0f, c=3.0f;

unsigned long long start = clock64();

#pragma unroll 128

for (int i = 0; i < iters; i++) {

a0 = fmaf(a0, b, c);

a1 = fmaf(a1, b, c);

a2 = fmaf(a2, b, c);

a3 = fmaf(a3, b, c);

a4 = fmaf(a4, b, c);

a5 = fmaf(a5, b, c);

a6 = fmaf(a6, b, c);

a7 = fmaf(a7, b, c);

}

unsigned long long end = clock64();

out[0] = (end - start);

out[1] = __float_as_uint(a0 + a1 + a2 + a3 + a4 + a5+ a6 + a7);

}

The above kernel run for 1 block and 1 thread produces the following output:

(base) umarkar@umarkar-desktop:~/Documents/microbenchmark_jetson_nano$ ./build/fma_throughput

cycles per FMA: 1.61471 Result: 2139095040

This result indicates a single CUDA core is able to schedule at most 1 FMA instruction per cycle.

Part 3.2: CUDA Core count

We now use this information to construct a kernel to saturate all CUDA cores in a Streaming Multiprocessor and use the saturation point to determine the number of CUDA cores. The kernel is a variation of the kernel used to determine the FMA instruction throughput. We construct a for loop of FMA operations, using 4 independent “streams” of calculations to make sure we completely saturate the ALU and only one thread can be resident per CORE.

__global__ void flop_kernel(float *out, int iterations) {

int idx = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

float x1 = 1.000001f;

float x2 = 1.000002f;

float x3 = 1.000003f;

float x4 = 1.000004f;

#pragma unroll 64

for (int i = 0; i < iterations; i++) {

x1 = x1 * 1.000001f + 0.000001f;

x2 = x2 * 1.000001f + 0.000001f;

x3 = x3 * 1.000001f + 0.000001f;

x4 = x4 * 1.000001f + 0.000001f;

}

out[idx] = x1 + x2 + x3 + x4;

}

This kernel is launched on a single block to make sure we only use a single SM and the number of threads is varied in steps of 8 threads. We use CUDA events to track the average kernel execution time:

__global__ void flop_kernel(float *out, int iterations) {

int idx = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

float x1 = 1.000001f;

float x2 = 1.000002f;

float x3 = 1.000003f;

float x4 = 1.000004f;

#pragma unroll 64

for (int i = 0; i < iterations; i++) {

x1 = x1 * 1.000001f + 0.000001f;

x2 = x2 * 1.000001f + 0.000001f;

x3 = x3 * 1.000001f + 0.000001f;

x4 = x4 * 1.000001f + 0.000001f;

}

out[idx] = x1 + x2 + x3 + x4;

}

#include <vector>

#include <numeric>

float mean(const std::vector<float>& values) {

if (values.empty()) return 0.0f;

float sum = std::accumulate(values.begin(), values.end(), 0.0f);

return sum / values.size();

}

float run_kernel(int threads, int iterations, int repeats=20) {

int blocks = 1;

int total_threads = threads;

float *d_out;

cudaMalloc(&d_out, total_threads * sizeof(float));

cudaEvent_t start, stop;

cudaEventCreate(&start);

cudaEventCreate(&stop);

// flop_kernel<<<1, threads>>>(d_out, iterations);

// cudaDeviceSynchronize();

float total_ms = 0.0f;

for (int r = 0; r < repeats; r++) {

cudaEventRecord(start);

flop_kernel<<<blocks, threads>>>(d_out, iterations);

cudaEventRecord(stop);

cudaEventSynchronize(stop);

float ms = 0.0f;

cudaEventElapsedTime(&ms, start, stop);

total_ms += ms;

}

cudaFree(d_out);

cudaEventDestroy(start);

cudaEventDestroy(stop);

return total_ms / repeats;

}

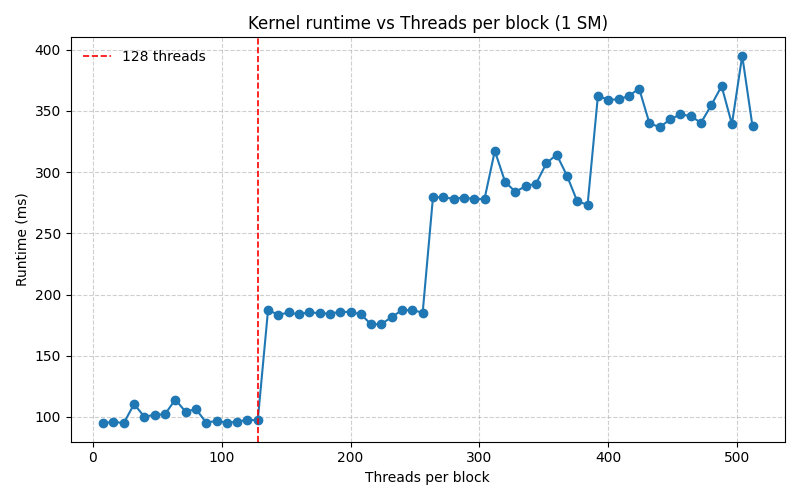

The graph below plots the execution time for varying thread counts:

The execution time stays more or less constant until 128 threads are launched, then it doubles and stays at that value until 256 threads are launched and so on. This is a clear indicator that up to 128 Threads can be resident on a single SM at once, indicating we have 128 CUDA cores per SM.

Part N+1: Work in progress

Next, I’ll explore how many blocks can be scheduled per Streaming Multiprocessor, memory latency, and cache behavior, using similar timing-based experiments. Stay tuned!